Climat en France- Pour préparer votre séjour à Paris

France’s climate is not uniform. Although France is only 1000 km from north to south, and slightly less from east to west, the climate, while not radically different from one region to another, does have its differences due to the country’s particular geographical position within Europe. It’s a good idea to be aware of these if you’re a tourist, so that you can make the necessary clothing and other arrangements to make the most of your stay.

In France, a generally temperate climate

What is climate? Climate is a synthetic representation of the meteorological conditions that characterize a given region. It is defined by the average values, generally over 30 years, of meteorological parameters (temperature, rainfall, wind, sunshine, etc.), but also by variations, extremes and specific phenomena such as fog, thunderstorms and hail.

Metropolitan France enjoys a temperate climate overall.

But in reality, and by refining the meteorological results, we find 5 types of climate for the whole of mainland France.

Five main types of climate in France

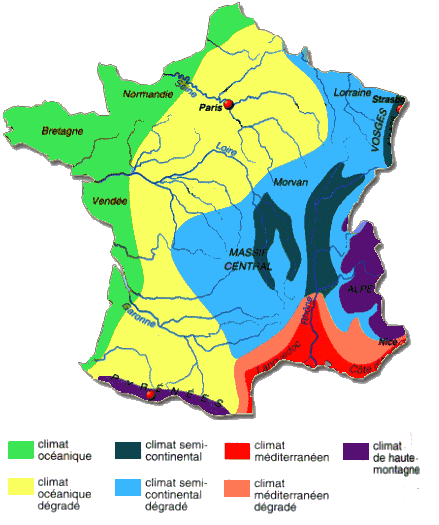

There are five main types of climate in mainland France:

- oceanic, along the coasts of the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean (in green on the map)

- altered oceanic (or degraded), the climate in Paris (yellow on the map)

- semi-continental (on the mountains in the center – in black) and degraded semi-continental in eastern France (in light blue)

- mountain, in the Alps on the Italian border and in the Pyrenees on the Spanish border (dark blue)

- Mediterranean, on the coast bordering the Mediterranean Sea (in red).

Why this nuanced, temperate climate?

There are several reasons for France’s climate

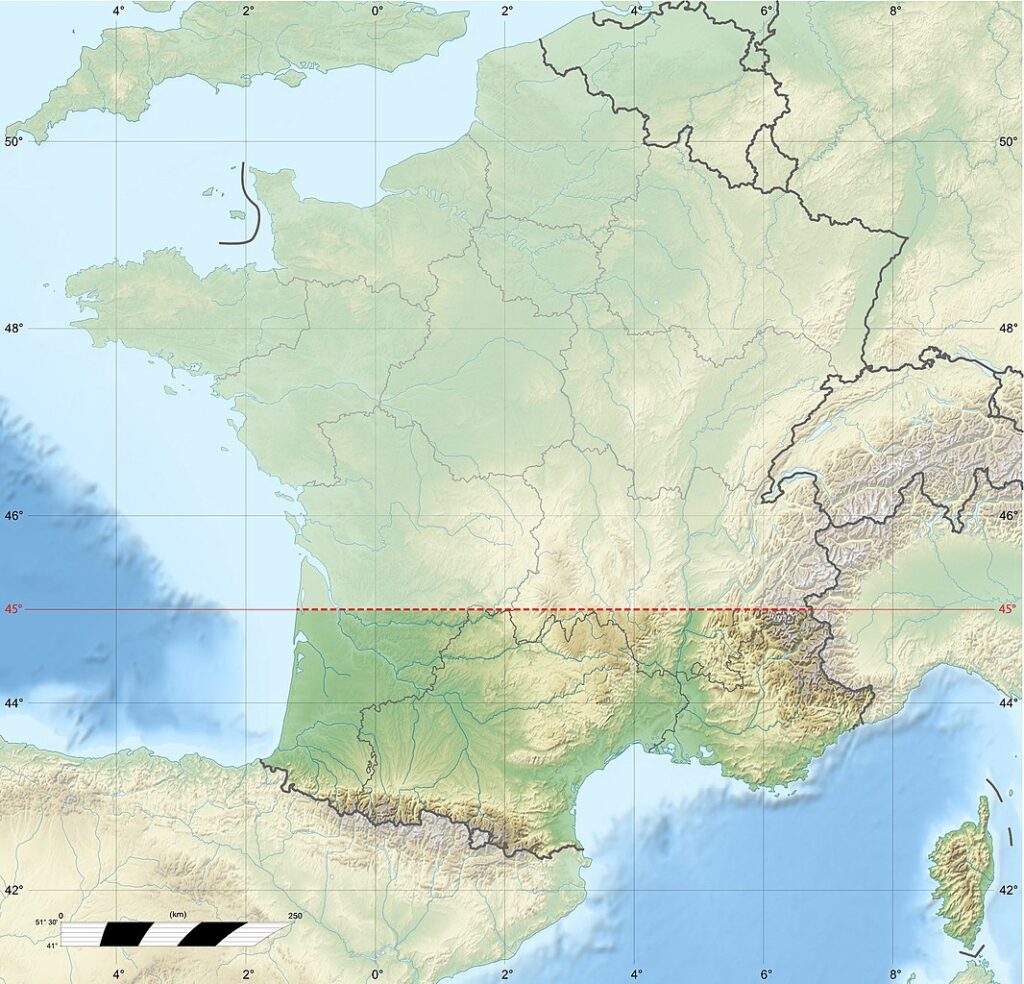

- France lies in the northern hemisphere, crossed by the 45° parallel of latitude, almost at the south-western tip of the European continent.

- Metropolitan France is bordered by some 5,500 km of coastline, either Atlantic (4,100 km approx.) or Mediterranean (1,694 km including Corsica 688 km), whereas France is only 1,000 km from north to south and 950 km from east to west.

- In addition, a warm marine current called the Gulf Stream (or North Atlantic Drift) is close to the Atlantic coast.

- The prevailing wind is naturally westerly, due to the Earth’s rotation, but disturbed by the high-pressure zone of the Azores anticyclone and its corollary low-pressure zone.

- The presence of high mountains on the eastern and south-eastern borders (Jura and Alps) and in the south (Pyrenees).

- Lower mountains in central France (Massif Central), western Brittany (Massif Armoricain) and the northeast (Vosges and Ardennes).

- The presence of a large central plain that descends from Belgium through the Paris region and Aquitaine to the Pyrenees mountain range.

- Rivers that have carved valleys from the Alps and Jura towards the Mediterranean and the North Sea, or from the Massif Central towards the North Sea or the Atlantic, or from the Pyrenees towards the Atlantic.

- The presence of the Mediterranean in south-eastern France, a virtually closed sea that also borders Africa.

- The 45th parallel passes near Bordeaux, Valence (France), which is 70 km south of Lyon and near Grenoble. That’s around 450 km south of Paris. France lies between latitudes 42.5° at the southern end and 51° at the northern end.

Latitude 45° is where the reference cultivation of vines on plains is best suited (before the general climate warms up in future years), hence the vintage wines of Bordeaux and the Rhône Valley. It’s also the average latitude at mid-distance (in degrees) between the equator and the North Pole. This is where temperate climates and temperatures are located.

In the USA, the 45° parallel runs south of Portland (Oregon), where vines are also grown, and north of Lake Michigan, through New York State and Quebec in Canada. And yet their climates have little in common with France. Why this is so, see below.

France is surrounded by water

Water has a thermoregulatory effect. The oceans “absorb” heat in summer and release it in winter. As a result, the lands they bathe benefit from this oceanic time delay, which “softens” the temperature differences between winter and summer.

Metropolitan France is bordered by approx. 5,500 km of coastline, either Atlantic (approx. 4,100 km) or Mediterranean (1,694 km including Corsica 688 km), although France is only 1,000 km from north to south and 950 km from east to west.

The presence of the Mediterranean in the south-east of France, a virtually closed sea, is warmed by the high temperatures encountered on the African coast. It is a reservoir of heat whose influence is particularly felt on the Côte d’Azur and in the south-east of the country (as well as in Italy and Spain).

The direct consequence of the presence of oceans and seas on the climate is that water temperatures change slowly with the seasons, warming the land in winter and cooling it in summer. On the other hand, oceans are the source of intense evaporation over huge surfaces, resulting in rainfall that is often short but repeated (oceanic climate) if the winds blow from the sea.

The Atlantic current of the Golf Stream

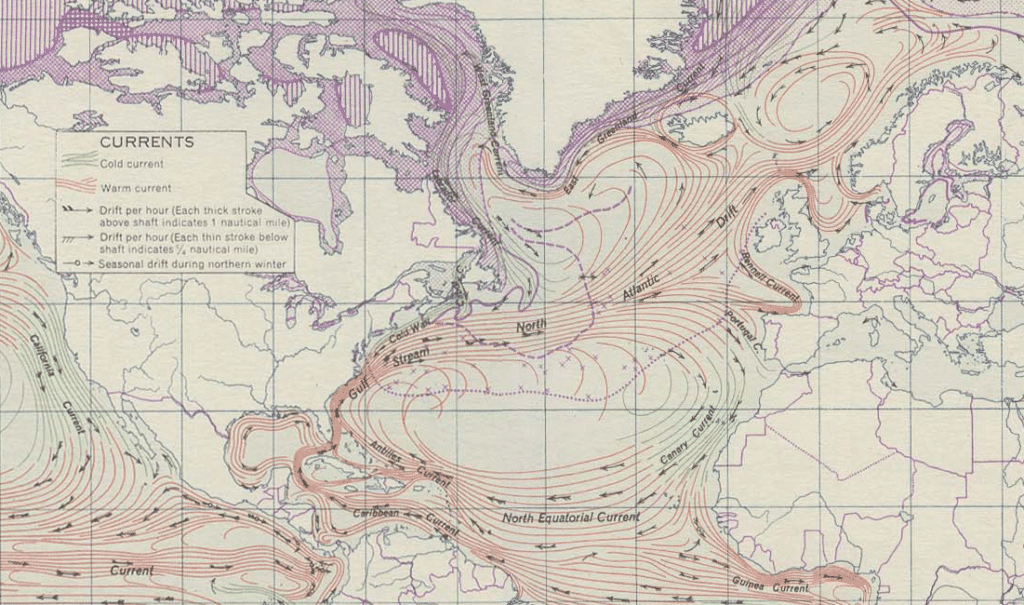

There is also a marine current known as the Gulf Stream (or North Atlantic Drift). This warm ocean current has been well known since the 16th century to navigators returning from the Americas.

It is extraordinarily powerful (displacing around 20 million cubic metres of water per second), and constant. It originates in the Caribbean, skirting the southern coast of the USA.

At Cape Hatteras in South Carolina, USA, it completely changes its appearance, disintegrating into a multitude of oceanic eddies that are clearly visible to satellites.

It’s part of a larger whole called the Atlantic Gyre. Some 20% of these water masses, driven by winds and the Earth’s rotation (equal to 20 times the flow of the Amazon), cross the Atlantic basin from west to east. It continues northwards, while the rest flows southwards.

So it’s not the Gulf Stream in its entirety that licks European shores, but a mathematically aggregated set of currents and eddies known as the Atlantic overturning circulation (Amoc). As a result, the water in the Atlantic is warmer than it should be. The land it washes therefore benefits from this additional heat. The west coast of France is one such area.

The Azores anticyclone

Because of the Earth’s rotation, atmospheric circulation is from west to east. As a result, the prevailing winds in France normally come from the west.

However, westerly winds are mild in France. In fact, as the air passes over the ocean, it warms up more than if it were flowing over land. For example, the westerly wind is cold in the eastern United States because it has traveled thousands of kilometers over land. This is not the case on Europe’s coasts, after the air has passed over the thousands of km of the North Atlantic.

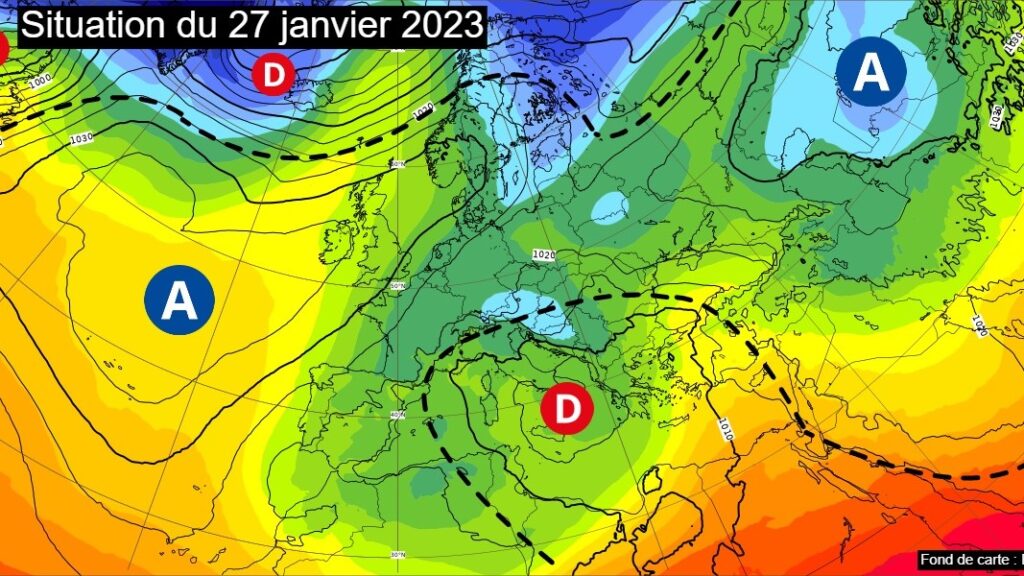

But nothing is so simple. The normal prevailing westerly wind is disturbed by the area of high atmospheric pressure known as the Azores High (A) and its corollary, the low-pressure area (D). Note that the anticyclone rotates clockwise, while the low-pressure zone rotates anti-clockwise.

The origin of anticyclones is high evaporation due to temperatures in the tropics (latitudes between 30° on either side of the equator), which creates a zone of depressions at the surface (in the tropics). This drags the air aloft, which then moves northwards towards Iceland. The air then cools and descends to the earth’s surface, creating atmospheric overpressure at low altitudes. This “heavier” air mass is reflected in the high atmospheric pressures that characterize the anticyclone.

The Azores anticyclone is created by the evaporation of the tropical Azores zone – hence its name, which changes to Bermuda anticyclone on the American side, as this zone moves to Bermuda in winter. But depending on the season and the temperature of the surrounding area (over a few thousand km), the “high pressure” zone labelled A on the maps below moves more or less towards Northern Europe and more or less over the Atlantic or even into the interior of the European continent.

Depending on the position of high and low pressure (marked D on the maps), the anticyclonic zone blocks the direct arrival of westerly winds. Winds always flow naturally (and physically) from high pressure (A) to low pressure (D). As a result, wind flows over France can ultimately come from almost any direction, with the exception of the east (or very rarely).

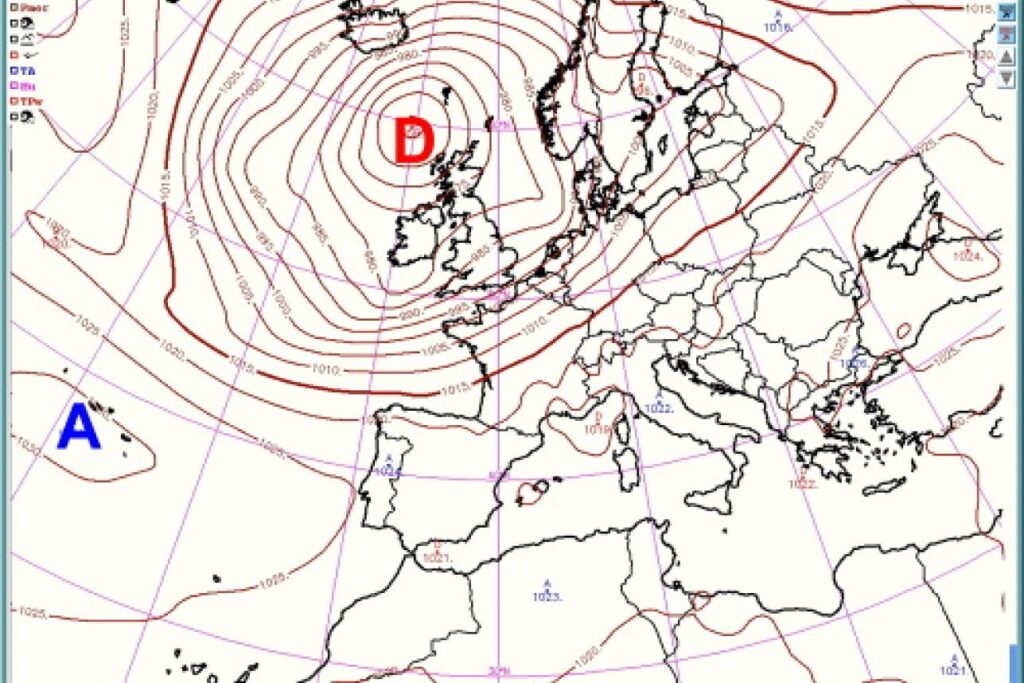

High (A) and low (D) pressure positions relative to France: south-westerly wind

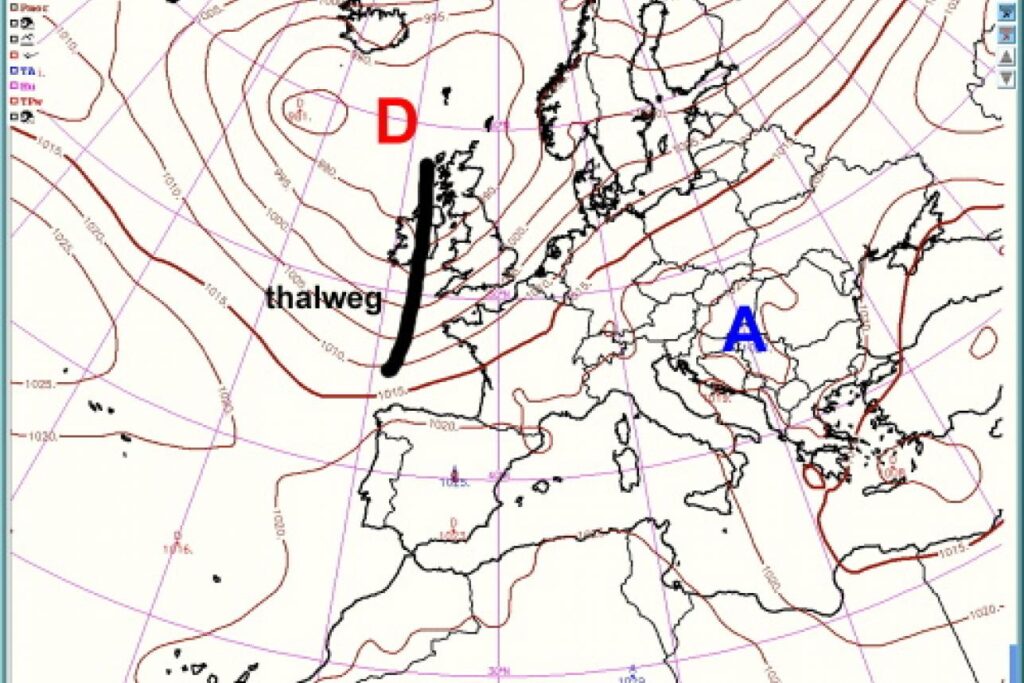

High (A) and low (D) pressure positions relative to France: southerly and easterly winds (Sirroco from the Sahara). Thalweg = low pressure

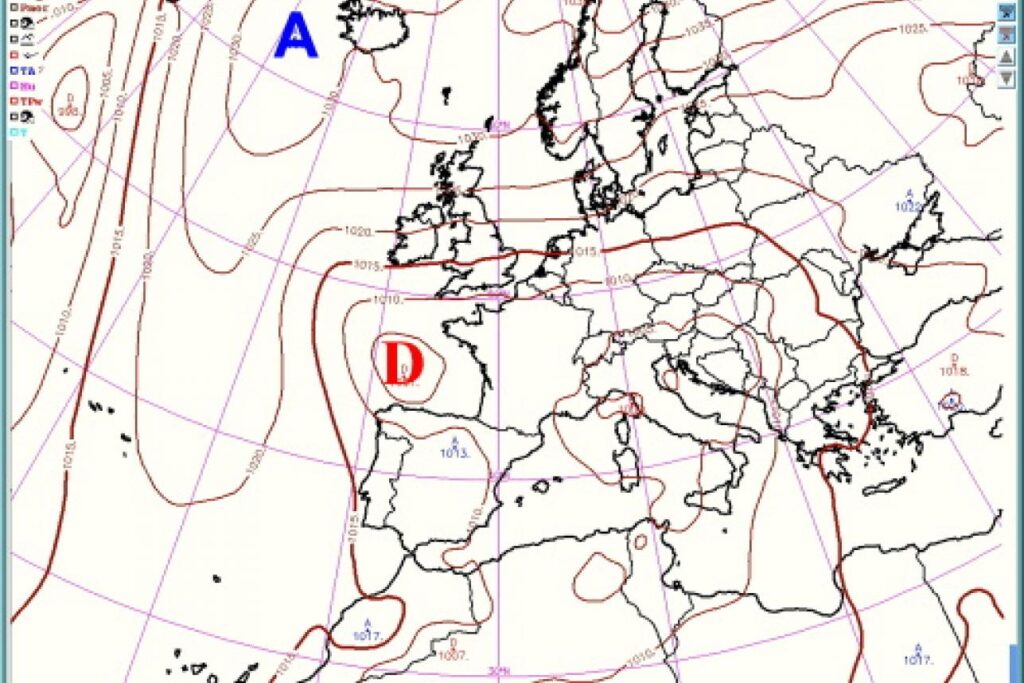

High (A) and low (D) pressure positions relative to France: northerly wind (from Russia and Siberia)

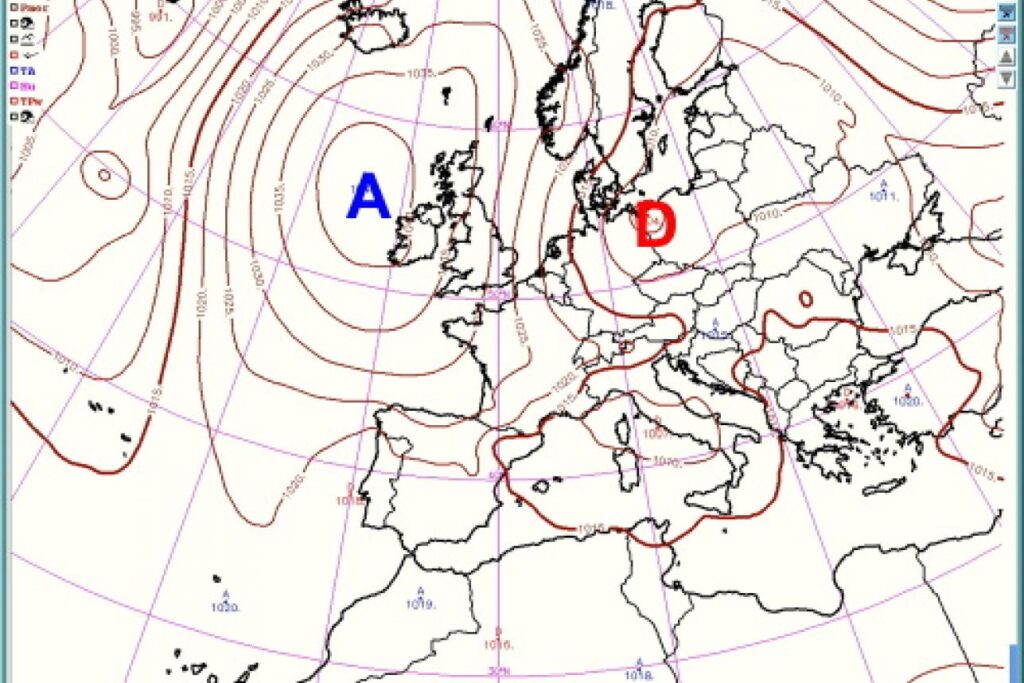

High (A) and low (D) pressure positions relative to France: westerly and rainy south-westerly winds

As a result, the position of the Azores anticyclone has a major influence on the climate in France. This makes it all the more difficult to forecast temperatures and rainfall, as this position changes from season to season (albeit following certain “rules”), even from week to week or day to day within the same season.

Relief, young and old mountains

Relief not only has a direct impact on its own (mountain) climate, but also on all the surrounding regions, such as plains and valleys. So it’s a good idea for tourists visiting France to have a clear idea of which mountains they’ll be crossing or staying in.

- The Alps border Switzerland and Italy to the east. The Alps extend as far east as Liechtenstein, Austria, southern Germany and Slovenia. They are young mountains formed during the Mesozoic (-252 to -66 million years ago) and the Cenozoic (since -66 million years ago). The Alps culminate at 4,806 metres on Mont Blanc1. There are 82 major peaks over 4,000 metres in altitude (48 in Switzerland, 38 in Italy and 24 in France). Mountain passes linking valleys and countries often exceed 2,000 metres in altitude. The Alps form a 1,200-kilometer barrier between the Mediterranean Sea and the Danube.

- The Jura mountains date from the Quaternary era (-2 million to -20,000 years ago). It peaks at 1720 m (Crêt de la Neige). It forms the boundary with part of Switzerland.

- The Vosges mountains to the north-east, with 14 peaks over 1,300 m in height (1424 m at Grand Ballon, the highest point). The original Hercynian chain, formed 300 million years ago, consists of granite and volcanic rock. Heavily eroded during the Secondary Era, this ancient massif was uplifted during the Tertiary Era by the formation of the Alps, before collapsing at its center to form the Rhine Graben (which allowed the Rhine River to flow through). The Vosges mountains and the Black Forest in Germany appear as a result of the Rhine collapse. They are evidence of one of the gigantic active faults that fractured Europe sixty-five million years ago at the beginning of the Tertiary era.

- The Pyrenees chain in the south between France and the Iberian Peninsula (Spain). 430 kilometers long, from the Mediterranean Sea (Cap de Creus) to the Bay of Biscay (Cap Higuer). It culminates at 3,404 meters altitude at the Aneto peak (Spain). The Pyrenees are a young mountain belonging to the alpine belt – dating back some 40 million years, but beginning to form in the Campanian period (between 80 and 70 million years ago) – born of the collision of two terrestrial plates, the Spanish and the European.

The Pyrenees are artificially divided into the Western, Central and Eastern Pyrenees. The central part is home to the highest peaks above 3,000 meters, such as the Aneto (highest peak in the Pyrenees at 3,404 meters) and the Vignemale (highest peak on the French side at 3,298 meters). There are few crossing points between France and Spain (Col de Puymorens);

- The Massif Central is the mountain range in central France. Less high because older and worn by erosion, it culminates at 1,885 meters at the volcanic summit of Puy de Sancy (south-west Puy-de-Dôme). On the whole, the Massif Central is an ancient Hercynian massif composed mainly of granitic and metamorphic rocks. It was formed 500 million years ago, although the causses and especially the volcanic reliefs are more recent. In fact, when it was formed 250 to 300 million years ago, the Alps collided with the eastern flank of the Massif Central to raise it up (and the development of the Alps towards the Pyrenees 180 million years later – did the same in the south-eastern part. As a result, numerous volcanoes appeared in the northern part of the Massif Central, which became a volcano “field”. Today, there are 80 (extinct) volcanoes, i.e. most of the volcanoes in mainland France. This part is known as the “Chaîne des Puys”, a tourist and hiking region. Covering 35 km, it includes 80 volcanoes ranging in height from 50 m to 500 m, on a granite plateau at an altitude of 1,000 metres. This northernmost group is the youngest: 95,000 to 8,500 years old (7,000 if we include the Pavin).

- The Armorican Massif, in Brittany, is the Breton orogenic phase, dating from the beginning of the Lower Carboniferous, or Tournaisian, period around 360 million years ago. Erosion has meant that high points rarely reach an altitude of 400 metres.

- The Ardennes is a small, ancient and now eroded massif located between France, Luxembourg and Belgium. The oldest Ardennes orogenic phase ended the Caledonian fold and began the Hercynian fold (at the start of the Lower Devonian, or Gedinnian, around 400 million years ago). The highest points are between 500 and 600 m, with the highest point at 694 m at the “Signal de Botrange” in Belgium.

- The Morvan. This is the smallest mid-mountain area in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region, bordering the departments of Côte-d’Or, Nièvre, Saône-et-Loire and Yonne. It covers an area of just 5,000 km², at low altitude (400 to 901 m, with an average altitude of around 600 m). It is a remnant of the Hercynian Massif, like the Massif Central and the Massif Armoricain. It is a barrier between the Paris Basin and the Saône Valley, and thus the Rhône, which required costly road and rail (TGV) works to cross it.

Rivers and valleys

The formation of the mountains naturally led to the evacuation of rainfall as directly as possible towards the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Rivers then carved out the valleys between the mountains. This has helped define France’s preferred means of communication, most of which run through the valleys.

In France, each mountain drains its waters via one or more rivers:Rivers and valleys The formation of the mountains naturally led to the evacuation of rainfall as directly as possible towards the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Rivers then carved out the valleys between the mountains. This has helped define France’s preferred means of communication, most of which run through the valleys. In France, each mountain drains its waters via one or more rivers:

- The Rhône Valley and its river, the Rhône, whose source is in the Swiss Alps.

- The Garonne Valley and its river of the same name, with its source in the Pyrenees Mountains

- The Loire Valley and its river, which rises in the Massif Central

- The Seine Valley and its river originating in the Morvan region

- The Alsace Plain and its river, the Rhine. Its source is in the Swiss Alps, close to the source of the Rhône. It flows through Liechtenstein, then Austria, returns to Switzerland, serves as the border between France and Germany, and then enters the Netherlands, where it flows into the North Sea, mixing with the Meuse, whose source is in the Vosges, close to the Saône, a tributary of the Rhône.

The valleys have created specific climatic conditions: mild temperatures as in the Loire Valley (Angevin climate) or the Mistral wind that “descends” from the north in the Rhône Valley, or a continental climate in the Rhine Valley (cold in winter, hot in summer).

The central plain

The great plain, almost the center of France, stretches from Belgium to the Pyrenees chain at the Spanish border in the south. It includes the Paris region (City of Paris) and the Aquitaine region (Bordeaux). This plain is swept by prevailing westerly winds from the Atlantic, which are rather mild but often damp. But for certain positions of the Azores anticyclone, this leaves the door wide open to winds from northern Europe or from Russia and Siberia. Which is less pleasant in winter.

The altered oceanic climate of Paris

The altered oceanic climate is a transition zone between oceanic, mountain and semi-continental climates. Temperature differences between winter and summer increase with distance from the sea. Rainfall is lower than at the seaside, except in the vicinity of relief. The altered oceanic climate concerns the western and northern foothills of the Massif Central, the Paris Basin, Champagne, eastern Picardy and Hauts-de-France. Paris is a case in point.

Parisian climate on the plain of the Paris Basin

Paris has an alternating oceanic climate, although the oceanic influence is much greater than the continental influence. Between 1981 and 2010, this meant fairly hot summers (June 1 to August 31) (average 19.7°C), mild winters (December 1 to February 28) (average 5.4°C), with frequent rainfall in all seasons and changeable weather, but with lower rainfall (637.4 millimeters) than on the coasts.

There are also a few temperature peaks (continental influence) in the middle of winter (when the anticyclone allows winds from Siberia to pass through) or in summer (when the Azores anticyclone is positioned to favor the rise of winds from the Sahara).

The increasing urbanization of Paris has led to a further rise in temperature (+2°C annual average compared with forested areas), as well as a reduction (disappearance) in the number of foggy days. However, when the temperature rises above 30°C, the low humidity and dew point make the heat bearable.

Sunshine amounts to 1,689.6 hours a year, which is relatively low (1,595 hours in the Monts d’Arrée in Brittany, 2,917 hours in Toulon to the south).

Winds are generally moderate (fifty days with gusts over 50 km/h), and predominantly from the west/southwest. However, there are always exceptions. On December 26, 1999, during the first major storm to sweep across Europe, gusts of over 220 km/h were recorded at the top of the Eiffel Tower (the absolute record for instantaneous speed since the first meteorological measurements were taken in 1873).

The 637.4 millimeters of precipitation are very evenly distributed throughout the year, with extreme values of 41.2 millimeters in February and 63.2 millimeters in May. Paris sees an average of 111.1 rainy days a year, but while these are frequent, they are not very sustained. On average, thunderstorms occur 18 days a year, mostly between May and August.

Since records began at Parc Montsouris (south of Paris), the driest year was 1921, with 271.4 millimetres, and the wettest was 2000, with over 900.8 millimetres.

Snowfall amounts to 12 days a year, but rarely lasts more than part of a day in Paris intra-muros.

The temperature in Paris

On average, temperatures exceed 25°C 50 days a year, and 30°C only 11 days a year. As a result of the conurbation’s heavy urbanization, the temperature in Paris can be 4°C higher than in the farthest suburbs at night and at sunrise.

[table id=50en /]

Paris weather forecasts

The above information is taken from our article URL…… This article also includes a 1-hour to 15-day weather forecast for Paris, as well as a 3-month trend, which is particularly important and useful for any visitor to Paris:

- when planning your stay in advance: when to go to Paris?

- a few days before your trip: what to wear for the next 4, 5 or 8 days in Paris

- when you’re in Paris: what to wear today: temperature, rain, changing your program to suit the weather?

- When you need to get around Paris: the weather in one hour or hour by hour over 2 days.